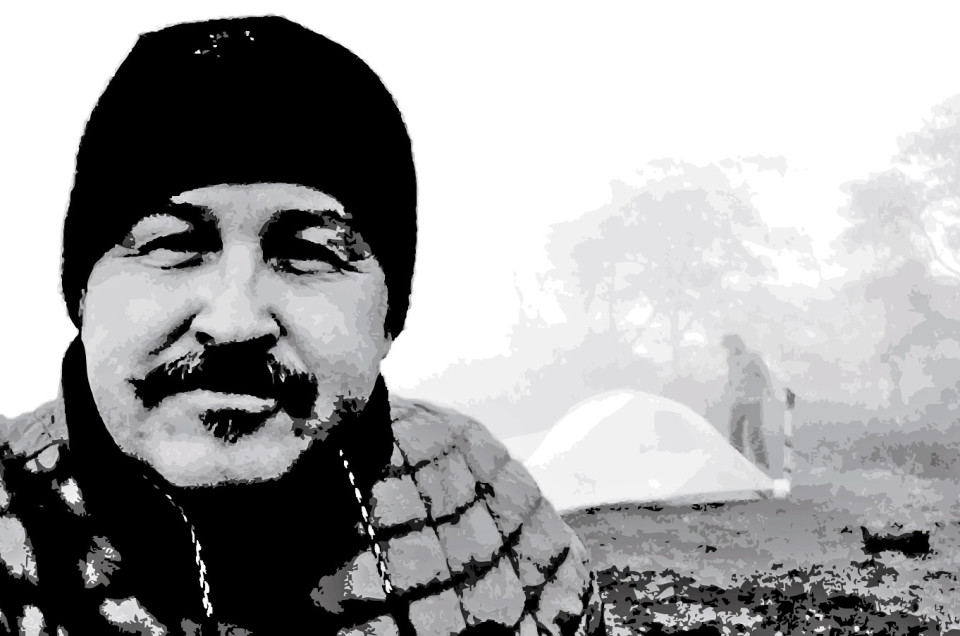

As I lay in my sleeping bag atop Tray Mountain last Wednesday night, the warmth from the fire Alexander had conjured out of a forest of wet wood radiated throughout the open shelter. That fire was as much a testament to his woodsman talents as it seemed a miracle to the rest of us. As only a fire can, it served to galvanize the group of strangers who, for at least one night, shared one another’s company. The hot coals cracked and popped, and the intoxicating scent of smokey air clung tightly to the confines of our dry shelter—and served as an ancient link to our distant past, a time when fire was a sacred tool, one which had the power to warm the heart and light the recesses of a dark mind.

With Alexander to my right, Mother Mary to my left, Yip and Yap in the middle, and Dave from Philadelphia and his buddy Paul from Atlanta on the other side of the enclosure, the shelter was full.

Then one last hiker—a young man named Juan—strolled in just before sunset. He was a recent FSU graduate in psychology and a resident of Pembroke Pines, Florida. And although he arrived late, he wasn’t disturbed at the prospect of sleeping in his hammock—despite the threat of rain. Juan joked that Hispanic people love hammocks, that it was his preferred method of sleeping on the trail. I liked his sense of humor and the way he deflected it upon himself as if it was his calling card, as if he was saying, “Yes, I may seem different. But if you give me a chance, I will prove my worth to your group.” That subtle skill is usually found only in much older persons. It is a method of coping developed by learning to fit in where you are the odd man out—which Juan, who had an ease and affability about him that spoke volumes about his past, had evidently had to do a lot. I was intrigued and wanted to learn more about his life. As it happened, I didn’t have to wait long.

With everyone tucked into their sleeping bags, Juan moved up to the fire and started a general conversation. I was tired and to be truthful dozing a bit. So I just lay there, one ear on the discussion and the other on the rise and fall of my chest. Every now and then I would throw in the occasional comment, mostly to let the others know I was still awake and listening, but I also wished to play a part in the mini-Chautauqua which had sprung up around Alexander’s special fire. The conversation meandered for awhile, weaving its way down a circuitous path which included talk of the trail, hiking gear, and a little bit about everyone present—where we each were from, why we were hiking, and how long our intended journey was. Of course the weather was important, and someone mentioned politics, but eventually the conversation focused on Juan. I snuggled up in my bag and listened intently as he told his amazing story.

It turns out that Juan is from Colombia—Medellin, to be precise, the second largest city in Colombia and home to the ruthless Medellin drug cartel. (When Juan said Medellin, I had the feeling we were in for one heck of a tale. He did not disappoint.) One day, when he was a small boy, the cartel thugs started a shootout in front of Juan’s house. His mother narrowly missed being killed by a wild bullet that burst through a window and into the sanctuary of their home. Juan’s uncle had been a cartel member, and it was unclear whether the shootout involved him or not, but that event was the last straw for Juan’s parents. They packed up their belongings and, through a lengthy process that included the help of friends, friends of friends, and deals made with the devil, they were finally allowed to immigrate to the U.S. The family settled in south Florida, a haven from the violence that had swirled around them in Colombia.

At this point in the story Juan became quiet. He played with a stick in the fire, the glow of embers lighting his sad face. He seemed to shrink as the orange light shone upon him. I was not the only one who sensed he was having trouble getting past this part. In that long moment, pregnant in its complete silence, we all just lay still, patiently waiting for Juan to continue. The only sound that could be heard was the occasional crack of hot sap as it ignited in the fire and a lone coyote howling in the distance.

Finally, he took up his story again. After a year or so, he told us, his father had to make a return trip to Colombia. There was unfinished business which remained in the life of this immigrant family, business only his father could finalize. Weeks went by. The weeks turned to months. But Juan’s father failed to return. Questions were asked. Inquiries made. But the lonesome reality was that Juan and his mother never found out what happened to his dad. “He may have been killed by the cartel bosses, or he may simply have chosen not to return to us,” he said. “Whichever it was, I have learned to get past it.” Then, with feigned bravado, he added, “I do not need him now.”

That was the only choice a young boy could make, I thought. The lesser of two horrific evils. My heart ached for him, and I assume the hearts of our other shelter mates were also breaking. But it perhaps touched me even deeper than it did the others, because I am on this incredible journey with my own son, who is almost the same age as Juan. This ill-fated young man would never have an experience like I was having with Alexander. He would never again experience the love of his own father, nor gain the closure that learning the truth of his father’s fate would bring. I stared into the darkness, tears welling in my eyes.

At this point, we were all completely silent for several minutes–even Yip and Yap. During that time, I heard Juan rearranging the logs in the fire, making the necessary adjustments he required in order to quell his nervousness and gain the courage to continue.

When he started again, he told us of his life with his mother. How she had raised him all by herself, alone in a new country, making a living for the both of them selling empanadas and arepas on the streets of Ft. Lauderdale. He told us how he would help her in the tiny kitchen of their home, shaping the dough, preparing the fillings, helping her to package the palm-sized treats in waxed paper or aluminum foil, or filling the coolers she used to hold her daily inventory. The way he shared this part of the story let us know that his love for his mother ran very deep. His descriptions of their time together and of the ingredients his mother used to make the products she sold each day were more brilliant, richer in the telling, more lively than the tragic tale he had told of his father.

He told us many times that she helped him to purchase the gear so he could make this trip. “My mother made this journey possible,” he said over and over again. I watched him while he continued his story, his hands making the sign of the cross—although I don’t think Juan was even aware of the gesture. I don’t know for sure what his purpose is out here on the Appalachian Trail. Not sure what he hopes to find. Maybe he is walking alone in the forest in search of his father. Maybe he is giving thanks to his mother. Maybe he is just walking to sort out the pain and loneliness he has hidden in the recesses of his soul. All of that is possible out here. The trail offers blessings—and absolution, too, if that is needed.

The last part of Juan’s story really struck home. He told us he wanted to pursue an education. But there remained a giant hurdle—he and his mother were illegal aliens, and until that changed, he could not enter college. He had been illegal for the sixteen years since his arrival from Colombia. It was the secret he carried most of his life; none of his friends knew about his status. When his thoughts turned to college, his mother retained an attorney so they could become naturalized citizens. It took five years and ten thousand dollars. That is a lot of empanadas and arepas. Juan made it through FSU on scholarship and graduated without student loans. He worked, and his mother supported him, too. He told me he really wants to go back and finish graduate school. He would like to be a counselor and help other people. I thought, What a fine young man. This is the kind of young man our society needs. This is the New American.

Today, there is so much talk about immigration, and our politics are filled with such fear, so much rhetoric about closing our borders—or worse, deporting people back to their countries of origin, regardless of the human implications—I worry that the state of the world is keeping us from upholding basic principles of freedom and equality. Historically, some of the worst atrocities have been committed when governments fall prey to the fear of the “other.” It is good to remember that, unless we are Native American, all our forebears arrived from other countries. My Holborn ancestors, for instance, came from England, and my mother’s family, from France and Canada.

Juan explained that his mother took a great risk just by beginning the naturalization process. Once the paperwork was filled out, she had essentially alerted the American immigration authorities that she and Juan were illegal aliens. Had they been deported back to Colombia, they would not have been able to return to the U.S. for ten years—and we would have lost the opportunity to welcome Juan and his courageous mother as citizens. To me, Juan and his mother represent the spirit of the American dream, an ideal that many people believe has been lost. I believe that as Americans our inclusive, warm-hearted compassion is our greatest strength.

I had the feeling Juan had not told this story to anyone in a very long time. But who better to tell than a group of strangers on the Appalachian Trail. I hope in the telling he gained a measure of relief. Juan’s is the story of so many people in the world today. Yet, in many ways it is a tragedy outside the bounds of anything most of us will ever encounter. I have to wonder how many times a day Juan’s story is repeated across America, and how many people’s lives and the futures of their children are held in the balance. As so often happens when I encounter stories from the opposite end of the spectrum of life from the one I occupy, hearing Juan’s story left me feeling both a sense of guilt for the great gifts that have come my way—and also feeling incredibly blessed.

* * *

In America, we do not go on religious pilgrimage like those of so many other countries. But I would have to characterize the seventy-some miles of trail I have encountered so far as truly sacred. I suppose we are far too Puritanical, in this country, to accept that a walk in the forest can be a sacred path to God. Only the structure of a church and the guidance of a priest can be that. But from my limited experience, the AT is our sacred walk, unofficial though it may be.

Tonight, Alexander and I met Juan for dinner at a great Mexican restaurant in Hiawassee. When we came off the trail on Friday, Juan took a shuttle bus to a nearby hiker hostel. As it turned out, the owner needed a shuttle driver, because the one he’d had quit the day Juan arrived. The owner also needed someone to help with incoming hikers, as October is a busy month on the AT. So Juan will remain here for another month, working and formulating his plans for the future—but tomorrow we will be in his company again, as we all walk the last miles of the Appalachian Trail in Georgia together. Juan said at dinner that he hopes to continue his walk on the AT.

It is my hope for him that he finds everything he is looking for.

3 Comments

Well said. I had many of the same thoughts. I was impressed by Juan and truly hope he is able to go back to school and finish his education, he certainly deserves the shot

teatime!

hello to you!

how rich your journey and experiences on the AT are. You are truly blessed to have made this choice and taken the opportunity. Happy hiking —hope the Mexican food gave you some jet propulsion

Wow, just wow.